By Dr. Fraser Thompson | Jul 27, 2025

FOAK or Fail: Why Australia Must Back First-of-a-Kind Clean-Energy Projects - and How to Do It

By Fraser Thompson (Cyan Ventures), with insights from David Yeh and Bernie Yoo (Precursor); and Julian Ryba-White (Mark1).

Historians may look back on this decade as the moment heavy-industry decarbonisation either leapt forward or stumbled. The deciding factor will be whether we can get enough first-of-a-kind (FOAK) projects out of the lab and into the ground. A FOAK is the first commercial-scale deployment of a technology or production pathway, usually 50- to 1,000 times larger than its pilot, built to prove that unit-costs, performance and regulatory compliance can hold in the real world.

FOAK can also be thought of from a sector perspective – helping overcome the various barriers (e.g., price gaps, regulation, supply chain, supporting infrastructure, etc.) to enable more sustainable technologies to replace incumbent technologies. Take sustainable aviation fuel for example – new technologies that can dramatically reduce the CO2 emissions of conventional jet fuel exist, but still face barriers related to price (up to 6x the price in some instances), regulation (e.g., blending rates), supply chains, and supporting infrastructure. These are barriers that are typically beyond the ability of any founder team to solve – it requires ecosystem curation. In Cyan Ventures, we refer to FOAK as ‘big bets’ – helping these new sustainable technologies deploy 2-5x faster than the current rates of deployment.

“FOAKs aren’t vanity projects; they’re the scaffolding of an entire zero-carbon industrial base.” (Fraser Thompson, Cyan Ventures)

So how do we do it? In this perspective piece, Fraser Thompson, Managing Partner of Cyan Ventures and former co-founder of Sun Cable has been understanding global approaches and spoke to three leading figures in the field – David Yeh and Bernie Yoo from Precursor and Julian Ryba-White from Mark1, to help better understand the opportunity, challenges and solutions related to FOAK projects.

- David Yeh is the founder of Precursor, the first advisory platform dedicated solely to FOAK. A former White House infrastructure lead and veteran climate investor, he has helped launch landmark projects and companies from Tesla’s first EV plant to being an early investor in Fervo Energy.

- Bernie Yoo is a partner at Precursor. A former Morgan Stanley energy & utilities banker, he was previously founder/CEO of an exited $100M revenue company as well as a venture-backed deeptech operator with significant experience scaling companies through public and private funding.

- Julian Ryba-White leads Mark1, a ‘developer-as-a-service’ venture spun out of Deep Science Ventures and RMI. Earlier, he cut his teeth inventing installation processes at SolarCity and co-founded Nokomis Energy, giving him a front-row seat to the pain points of scaling novel hardware.

In this perspective piece, we explore four key questions:

1. Why FOAK projects matter?

2. What makes FOAK projects so challenging?

3. What are some of the solutions to FOAK projects?

4. And what have we learnt from “developer as a service” models to support these projects?

1. Why FOAK projects matter

Australia is blessed with sun, wind and world-class mineral deposits, yet the real prize is converting those advantages into exportable low-carbon products:

- Green iron – Pilbara ore processed via hydrogen direct-reduced iron (DRI) can keep our ~A$130 billion iron-ore trade alive in a world that no longer buys coal-based steel. Recent pilots in Western Australia show the chemistry works; what’s missing is a commercial-scale pioneer.

- Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) – Australia has large advantages with feedstocks and the opportunity to derisk a sector responsible for 2% of global emissions, but there is a limited pipeline of projects to date.

- Advanced batteries, new solar cell technologies and other clean tech manufacturing opportunities – all require at least one domestic FOAK to prove cost curves and supply-chain readiness.

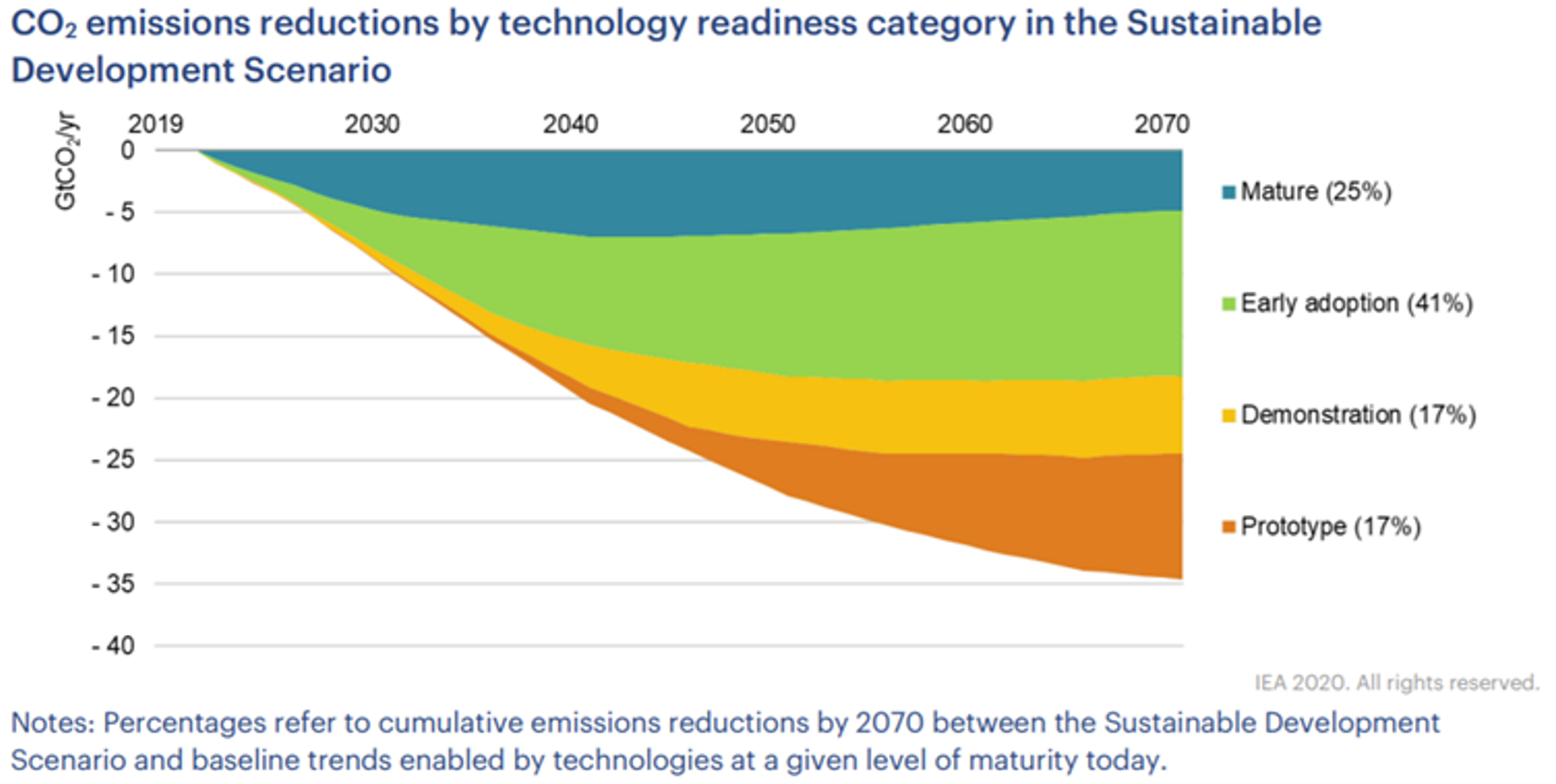

Globally, the IEA calculates that around 34% of the cumulative CO2 emissions reductions needed to shift to a sustainable path[1] come from technologies currently at the prototype or demonstration phase. A further 41% of the reductions rely on technologies not yet commercially deployed on a mass-market scale.[2] If we miss the FOAK window, we miss net zero.

Exhibit 1: The importance of FOAK projects (IEA, 2020)[3]

In investment terms, the IEA estimates annual average investments in technologies that are currently only at prototype or demonstration stages will need to reach US$350 billion per annum through to 2040, and nearly US$3 trillion in the 2060s.[4]

2. Why FOAKs are so hard - and the myths that slow us down

“Infrastructure investors are like film studio execs and want to back the Fast and the Furious 11. They don’t love independent art films made by first time director-writers” quips David Yeh of Precursor.

Capital scarcity is only the headline challenge. Other challenges include:

- Expertise bottleneck – “What kills a FOAK isn’t lack of money; it’s the fifteen people who know both fermentation skids and EPC contracts,” notes Julian Ryba-White of Mark1.

- Unproven supply chains – supply chain logistics are the “silent killer” of FOAK. Supply chain buyers and planners face the extraordinary challenge of figuring out demand, inventory levels, delivery logistics, working capital dynamics and much more all while standing up a supply chain that doesn’t yet exist. Bill of Materials (BOM) forecasting and management is an underappreciated trigger for ballooning FOAK costs. This does not even factor in global tariffs.

- Policy lag – permitting frameworks built for coal or gas plants rarely map neatly onto hybrid bio-industrial assets.

The result: the dreaded “valley of death” between grant-funded and venture-backed pilots and bank-financed scale-ups.

There are also some common myths with FOAK projects, such as:

- Myth 1 – “It’s just like launching software.” You can’t A/B-test a US$30 billion green iron pathway: bugs cost millions, not minutes.

- Myth 2 – “Capital is the only constraint." A technology company, a development company and an asset management company are three separate businesses – all are needed with these projects, but all require different skills” says Julian.

- Myth 3 – “Copy-paste designs from overseas.” Supply chains are local; lead-times balloon when bespoke valves land 9 months late.

- Myth 4 – “Regulators cheer innovation.” Permitting regimes are often built for fossil fuel incumbents and often leave a yawning gap for new green solutions.

- Myth 5 – “You can hack project finance or learn it on the fly”. Project development for conventional assets is hard. Doing a FOAK project with a rookie team is really HARD.

3. How to tilt the odds

Much has been written about the supply-side support for FOAK projects, from production tax credits through to grants and concessional financing. In the experience of Cyan Ventures, two areas often get overlooked:

- Locking in demand mechanisms. A key issue with FOAK projects is that they are often several times more expensive than incumbent technologies before technology learning curves and scale effects can kick in. Even with supply-side support, there is still typically a large gap. For example, Cyan Ventures analysis has shown that in green iron, there can still be an over 30% price gap with traditional iron processes, even after incorporating production tax credits and other benefits. So how to fill the gap? We believe more focus needs to be on establishing clear demand-side signals, whether that be mandates (see our previous article on sustainable aviation fuel mandate design), two-sided auctions (such as those used for green hydrogen in Europe), development of "book and claim’’ markets (e.g., renewable energy certificates, SAF credits), or buyer coalitions. Government can play an important role in orchestrating this. A government underwrite can reduce discount rates by up to 2-3% in some sectors, which translates to millions of dollars in savings. In the UK, Contracts-for-Difference are moving on from focusing on traditional areas like renewable energy generation, to now being applied to FOAK sectors like sustainable aviation fuels.

- Supporting developer teams. Another aspect is support for developer teams. In FOAK sectors in particular, it is very hard for startups to cover the full range of challenges they will face, from regulatory reforms through to designing innovative offtake contracts. The US Department of Energy pioneered a concept called “adoption readiness”, which looks at barriers to widespread adoption of a new technology. They look at 17 different dimensions, from the downstream value chain through to licence to operate. Based on Cyan Venture’s experience in Australia working with startups, it is extremely difficult to expect founder teams to manage this broad array of risk factors by themselves. To put it another way, a FOAK project requires integration of a technology company, a development company and an asset management company – each has a different business model and unique set of risks. Fortunately, there are some innovative approaches in this area, which we explore in the next section.

4. Lessons from running DaaS in the wild

Developer as a service (DaaS) firms embed veteran project-developers inside tech start-ups, taking joint responsibility for permitting, EPC oversight, capital strategy and offtake negotiations - until the venture can fly solo.

How Precursor works. “We act as a ‘Chief FOAK Officer’, working as embedded senior practitioners driving execution while partnering with founders from seed to demo to gigafactory: financing, risk, partners—and teaching them to how to fish and hence run the process in the near future,” says David.

How Mark1 works. Julian’s team enters in two phases: a planning sprint to map risks and budgets (‘measuring twice, cutting once’) and a co-development phase where Mark1 shares equity and milestone-based fees, “like the project-management conductor, occasionally picking up a violin when needed.”

David and Julian shared some of the lessons from the trenches:

- Incentives > invoices. Both firms tie compensation to value-add outcomes, not billable hours - aligning everyone with total-installed-cost, timelines and scope. As David noted, “We’re consistently being asked to find the hardest-to-find capital, so in response to that demand we’re securing the licensing necessary to expand our strategic advisory model and fully support our companies’ financing needs at both TopCo and Project.”

- DaaS requires a founder rethink. Developer as a service model is still a somewhat nascent concept, and can require founder teams to revisit whether they internally have all the necessary people and skills to do a FOAK and how much is really outsourceable. As Julian describes it, “technology is only valuated if it is deployed in a profitable asset – technology needs to be married with effective development and asset management to do this.”

- Take time to plan. Having a real detailed understanding of the founder team and the gaps is crucial to determine the project feasibility and the appropriate level of support. “We can take anywhere from 1 to 6 months with some projects just on the planning phase – but it is crucial to ensure our collaboration works” says Julian. To use the well-known adage, doing it alone may allow you to go fast, but getting the right collaboration allows a project to go far.

- Marry grey hair with start-up pace. A 30-year EPC expert plus a 30-year-old PHd out-perform two of either. As David relates, “an investor once told me they wouldn’t trust a particular company’s team to build a townhouse, let alone an 8-figure manufacturing facility. High IQ and fancy degrees help, but it doesn’t replace having done things for decades.”

- Align scope early. “Getting the scope and scale right on large scale industrial projects is crucial – otherwise project complexity will be the death of the project” says Julian.

- Plan the hand-back early. “Our core philosophy is embedded in teaching you how to fish” David reminds founders. “The ‘hold-my-beer” strategy of turning it over to outside parties doesn’t work in FOAK. You have to live and breathe the project execution and delivery.”

- Focus on continuous learning. Mark1 publishes post-mortems so each FOAK lowers the next one’s hurdle rate. “Technology developers aren’t project developers, and vice-versa, we bridge that gap until the skills converge,” Julian notes. David frames it this way: “The hardest cheque to write isn’t the last, it’s the first, because nobody on the team has walked that exact road before.” The DaaS model shortens that road.

Where to from here?

Australia has all the ingredients to be a global leader in the clean energy transition. But if we don’t crack the code on supporting FOAK projects, our plans will be stuck in white papers. Learning from overseas on innovative models such as establishing clarity on demand signals and exploring developer as a service models, are two potentially missing pieces in the jigsaw of realising our potential.

References:

[1] This scenario aims to align the global energy sector with the goals of the Paris Agreement, including limiting global warming to well below 2°C, while also achieving universal access to modern energy and improving air quality. It envisions net-zero emissions from the energy sector by 2070.

[2] IEA (2020), Energy Technology Perspectives 2020. Available at: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/04dc5d08-4e45-447d-a0c1-d76b5ac43987/Energy_Technology_Perspectives_2020_-_Special_Report_on_Clean_Energy_Innovation.pdf

[3] The IEA uses the following definitions for the 4 categories: Prototype: A concept is developed into a design, and then into a prototype for a new device (e.g. a furnace that produces steel with pure hydrogen instead of coal; Demonstration: The first examples of a new technology are introduced at the size of a full-scale commercial unit (e.g. a system that captures CO2 emissions from cement plants); Early adoption: At this stage, there is still a cost and performance gap with established technologies, which policy attention must address; Mature: As deployment progresses, the product moves into the mainstream as a common choice for new purchases.

[4] IEA (2020), Energy Technology Perspectives 2020. Available at: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/04dc5d08-4e45-447d-a0c1-d76b5ac43987/Energy_Technology_Perspectives_2020_-_Special_Report_on_Clean_Energy_Innovation.pdf

- Dr. Fraser Thompson

Need a problem solved? Let`s work together to solve it

Contact UsShare with