By Dr. Fraser Thompson | Jul 7, 2025

Jet Green, Spend Lean: Crafting Australia’s SAF Mandate

Low-carbon liquid fuels (LCLF)— think sustainable biofuels and synthetic e-fuels—are the workhorses of deep decarbonisation. They slip straight into aircraft, ships, heavy trucks and high-heat industrial processes where batteries and electrification still stumble, cutting lifecycle greenhouse-gas emissions without tearing up the existing fuel supply chain. Few countries are better placed to make these fuels than Australia. Abundant renewables, large tracts of marginal land, world-class ports and rail, and comparatively low financing costs give us a natural edge. A domestic LCLF industry would do more than slash emissions: it would boost fuel security, keep tourism and air-cargo customers onside as sustainability scrutiny grows, and lock in a credible pathway to net-zero by 2050.

The question is how to get momentum into a sector that barely exists today. Cyan Ventures’ analysis of global markets points to a handful of “tipping points” that turn promise into projects. Australia is ticking many of them, but one big missing piece is a hard demand and investment signal. Can a mandate—or another demand-side lever—fill that gap without blowing out costs? The Federal Government has earmarked AUD1.5 million to find out, commissioning a two-year regulatory-impact study starting 2024-25. This article aims to inform the discussion by offering perspectives on three core questions:

1. Why does Australia need a demand signal for LCLF?

2. What price tag might come with it and is it affordable?

3. How can international experience guide a mandate that is effective, efficient and fair?

1. Why does Australia need a demand signal for LCLF?

There are different ways of stimulating demand, ranging from subsidies through to public procurement. However, the most common approach used internationally is a future SAF use volume requirement (often described as a mandate or levy), where airlines or fuel suppliers are required to purchase a certain share of their jet fuel use from certified sustainable supply chains (which is typically coupled with supply-side support to manage costs). Most countries with flights to/from Australia are developing mandatory targets. For example, Singapore, Taiwan and Thailand have all established SAF mandates, requiring 5% blend by 2030. In Japan, they have legislated a more ambitious goal of 10% blend by 2030.

A demand signal is crucial for several reasons:

It sends a clear signal to investors and project developers to prioritise focus on the sector, which in turn can support foreign direct investment, local economic development from SAF production, fuel security and the competitiveness of our airlines.

It addresses market failures such as unpriced externalities, particularly the absence of a carbon tax, in Australia.

It provides a low cost “insurance policy” against the risk of green-conscious consumers not travelling or purchasing Australian air cargo. For example, 82% of Australians believe it’s important to find ways to reduce carbon emissions produced by air travel.[1] It is also crucial for international visitors. 81% of international travellers want to know if their airline is using SAF.[2] Australia’s event industry has already warned that carbon-focused corporates may “take their conferences elsewhere” unless domestic SAF production scales up.[3]

2. What price tag might come with it and is it affordable?

Think a mandate will blow out airfares? Think again. Sustainable Aviation Fuel’s core advantage is that it’s a drop-in fuel: it runs through the same hydrant trucks, pipelines and wing tanks as kerosene and can be blended at any ratio. That means Australia can start with a deliberately small blend—one or two per cent—while SAF is still pricey, then ratchet up as local supply scales and costs fall.

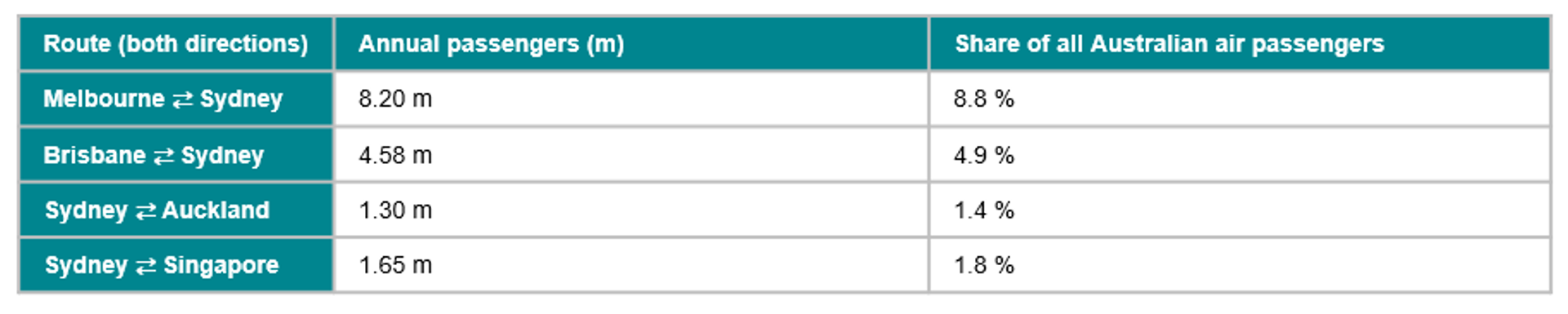

To see what that looks like in practice, Cyan Ventures modelled the fare impact on Australia’s busiest domestic and international routes. The result: the extra cost shows up in spare change, not sticker shock (see Table 1).

Table 1: Analysis of most popular aviation routes in Australia

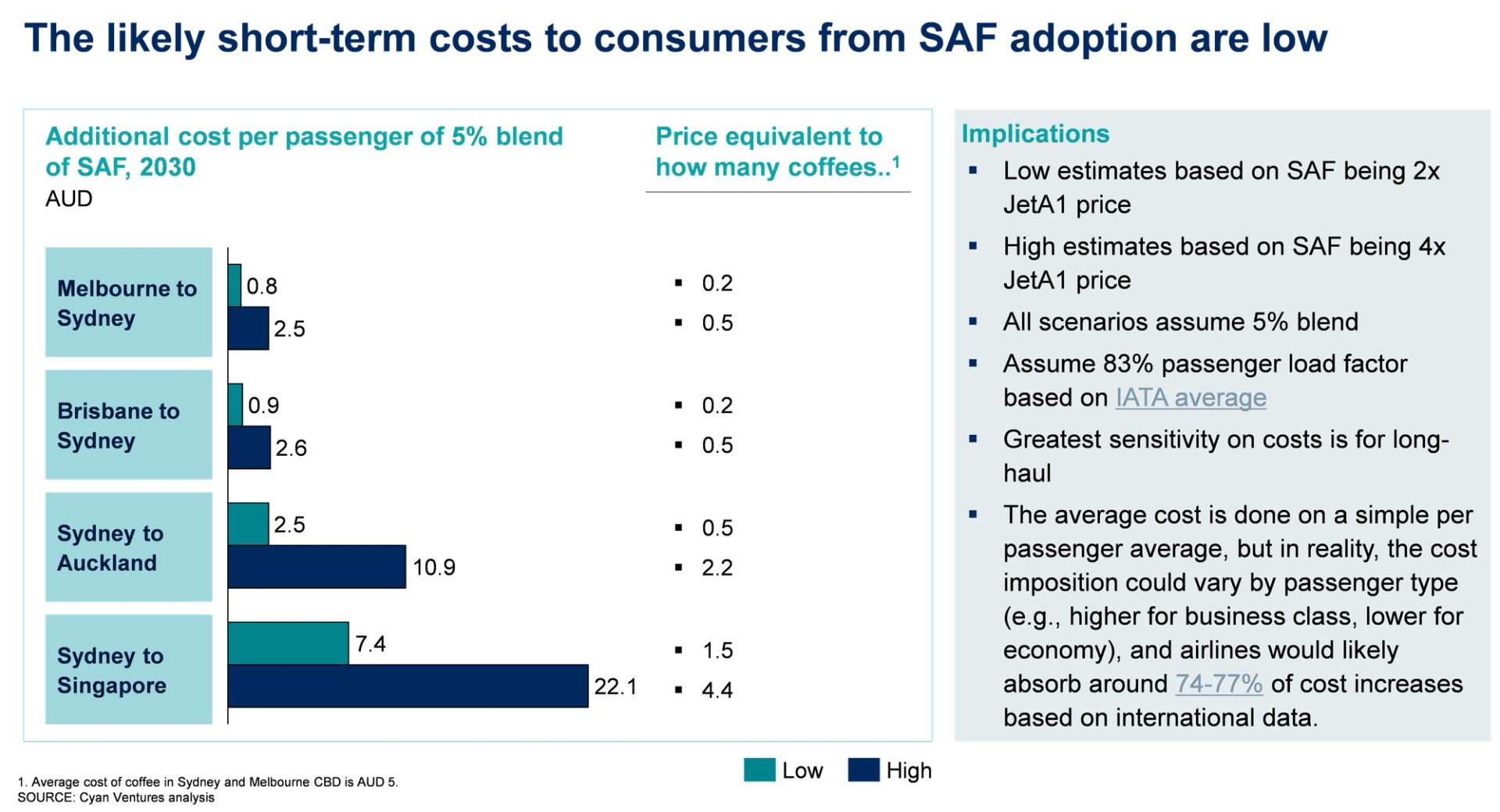

Cyan Ventures analysis shows that a mechanism legislating a 5% blend of SAF in 2030 in Australia – in line with regional peers like Singapore, Thailand and Taiwan and global government goals – would have a minimal impact on individual passenger costs. For example, for domestic routes, it would generally be less than a cup of coffee, and even on international routes (e.g., Sydney to Singapore), the likely cost could as low as AUD7.40 (Exhibit 1). While some could argue that given the low cost, why don’t airlines just do it themselves, a mandate is crucial for establishing a level playing field in an industry where margins can be tight, and also to send a clear long-term signal to investors and project developers.

Exhibit 1: Impact of 5% SAF mandate on Australian flight tickets

The economic upside from a SAF mandate is significant. For example, ICF has conducted analysis (on behalf of Airbus and Qantas) to examine economic benefits of SAF production in Australia.[4] The research finds that SAF production has the potential to contribute approximately AUD13 billion in GDP per year by 2040, while supporting nearly 13,000 full-time equivalent jobs in the feedstock supply chain and creating 5,000 new high-value jobs to construct and run the facilities.

3. How do you design it properly?

While implementation of SAF mandates internationally is still nascent, there are some useful lessons for Australia. For example, in Europe, there have been challenges with compliance fees (i.e., the fees fuel suppliers pass onto airlines to comply with regulations) which have effectively doubled the cost of meeting mandates.[5] Cyan Ventures has studied the design mechanisms of mandates, and four lessons are particularly noteworthy in the Australian context:

1) Size the mandate to match real, near-term domestic supply. Europe will just about hit its 2025 target only by siphoning fuel from other regions; that is a warning sign. Australia has the feedstock, but the project pipeline is thin. Matching the targets of regional peers in 2030 is realistic—provided ARENA’s AUD250 m program is paired with hands-on help for first-of-a-kind plants (project finance coaching, offtake brokering, EPC wrap support). Australia should consider reviewing the target every two years and explicitly incorporate domestic development progress.

2) Build in a cost-containment and credit-flex system. Under this system, each litre of SAF above the mandated blend earns the supplier a tradeable SAF credit; each litre short creates a deficit. Suppliers can bank surplus credits for up to three years or borrow against future production. This cushions airlines if a refinery outage or feedstock spike hits supply. Credits can also be sold between suppliers, so the cheapest producer meets extra demand first—driving overall costs down. A safety valve is crucial - if a supplier still sits on a deficit after the banking window, it pays a fixed penalty, capped at a policy-defined level such as the social cost of carbon (≈ A$200 t/CO₂-e). That ceiling prevents runaway compliance surcharges like those now hitting EU carriers.

3) Keep compliance flexible by pooling across airports. Instead of forcing every Australian airport to hit the exact blend each quarter, allow fuel companies to meet the target in aggregate across the national network.

4) Protect equity for price-sensitive and regional routes. Thin routes (e.g., remote communities with <100 000 seats / year) have little ability to absorb higher fuel prices. There are options to support these routes, such as recycling a slice of penalty revenue into a Remote Aviation Fund, or provide a per-seat rebate funded from SAF credit auctions.

***

Australia can and should win in the development of low carbon liquid fuels. Establishing a well-designed SAF mandate is both cost effective and crucial for catalysing investment and project development to realise that ambition.

[1] Tourism and Transport Forum (2024), “Tourism needs government support for green fuel to fly high”. Available at: https://ttf.org.au/tourism-needs-government-support-for-green-fuel-to-fly-high/

[2] Survey from IATA (July 2024). Information available at: https://www.iata.org/en/iata-repository/publications/economic-reports/air-travelers-views-on-saf-highlight-a-range-of-issues/

[3] For further information see: https://www.theaustralian.com.au/subscribe/news/1/?sourceCode=TAWEB_WRE170_a&dest=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.theaustralian.com.au%2Fbusiness%2Faviation%2Fcarbon-emissions-a-threat-to-future-events-on-the-scale-of-taylor-swift-says-ttf%2Fnews-story%2Ff8c7a94f9d28adf69b1545ebd4fbb4ac&memtype=anonymous&mode=premium&v21=HIGH-Segment-1-SCORE&V21spcbehaviour=append

[4] ICF (November 2023), Developing a SAF industry to decarbonise Australian aviation. Available at: https://www.qantas.com/content/dam/qantas/pdfs/qantas-group/icf-report-australia-saf-policy-analysis-nov23.pdf

[5] For further information, see https://www.iata.org/en/iata-repository/publications/economic-reports/excessive-saf-fees-in-the-eu--a-lost-opportunity-to-abate-2.7-million-tonnes-of-co2#:~:text=The%20fees%20imposed%20on%20airlines,assessed%20by%20price%20reporting%20agencies.&text=Given%20the%2042%20million%20tonnes,to%20abate%20less%20is%20unacceptable.&text=Terms%20and%20Conditions%20for%20the,do%20not%20use%20this%20report.

- Dr. Fraser Thompson

Need a problem solved? Let`s work together to solve it

Contact UsShare with