By Dr. Fraser Thompson | Aug 25, 2025

Beyond Learning Curves: A Practical Way to Judge Competitiveness Across Green Industries

Australia’s Productivity Commission has been clear that public support for the net-zero transition should rest on a hard fact base. In its interim report on Investing in cheaper, cleaner energy and the net zero transformation, Commissioner Barry Sterland framed the task bluntly: “Australia’s net zero transformation is well under way. Getting the rest of the way at the lowest possible cost is central to our productivity challenge.”

Taking that brief seriously means understanding what actually drives competitiveness in each clean-energy sector—and recognising that those drivers differ, sometimes dramatically. A single yardstick—say, comparing “learning rates” and assuming the biggest number deserves the biggest subsidy can mislead. Some sectors do thrive on classic “learning-by-doing”; others are constrained by input costs, infrastructure, or bankable demand, where early action can still be justified even if learning rates are modest. This perspective is crucial for understanding how to properly support different clean-energy sectors.

In this perspective piece, we sketch out lessons from the work of Cyan Ventures in supporting “first-of-a-kind” (FOAK) projects – that is, the first commercial-scale deployment of a technology or production pathway. We start by outlining the different competitiveness drivers for these projects, show how they compare across different sectors, and then discuss implications for policy support. A quick heads-up - there are a few acronyms and bits of industry shorthand ahead. I’ve tried to keep the jargon light and only where necessary to make this accessible to a non-technical audience.

1. What drives competitiveness in first-of-a-kind projects and sectors

Competitiveness of FOAK projects (and sectors) is driven by six factors:

1. Inputs – this relates to reducing the cost of feedstocks, power, ore quality, labour, etc.

2. Scale & learning – this relates to the experience-curve transitioning from First of a Kind (FOAK) to Next of a Kind (NOAK). Learning curves (aka Wright’s law; in solar often called Swanson’s law) are scale-based: every time cumulative production doubles, unit cost falls by a constant percentage (the learning rate).

3. System – this relates to the supporting implementation infrastructure including logistics and repeatable EPC and Balance of Plant (BoP) operations. In Australia, given the remoteness of supply locations and the export requirements for many opportunities, logistics becomes crucial for competitiveness.

4. Demand – this relates to factors that create a clear demand signal (e.g., mandates, standards, contracts for difference) with significantly reduce financing costs and enable scale.

5. Finance & risk – this relates to other factors that can reduce financing costs, such as blended finance.

6. Capability & institutions – this relates to the supporting skills and institutions for project development including permitting and construction.

Some may be surprised that technology is not in this list. Technology is of course crucial and requires a strong focus with R&D support and early stage commercialisation. However, that only gets us so far. It is scaling existing technologies that is crucial for our clean energy transition and productivity. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates roughly one‑third of cumulative emissions reductions rely on technologies in prototype or demonstration, and a further ~40% on technologies not yet deployed at mass market. Technology is also embedded in the different drivers – for example, new technologies to bring innovative plant feedstocks into supply are crucial for supporting low-carbon liquid fuel competitiveness.

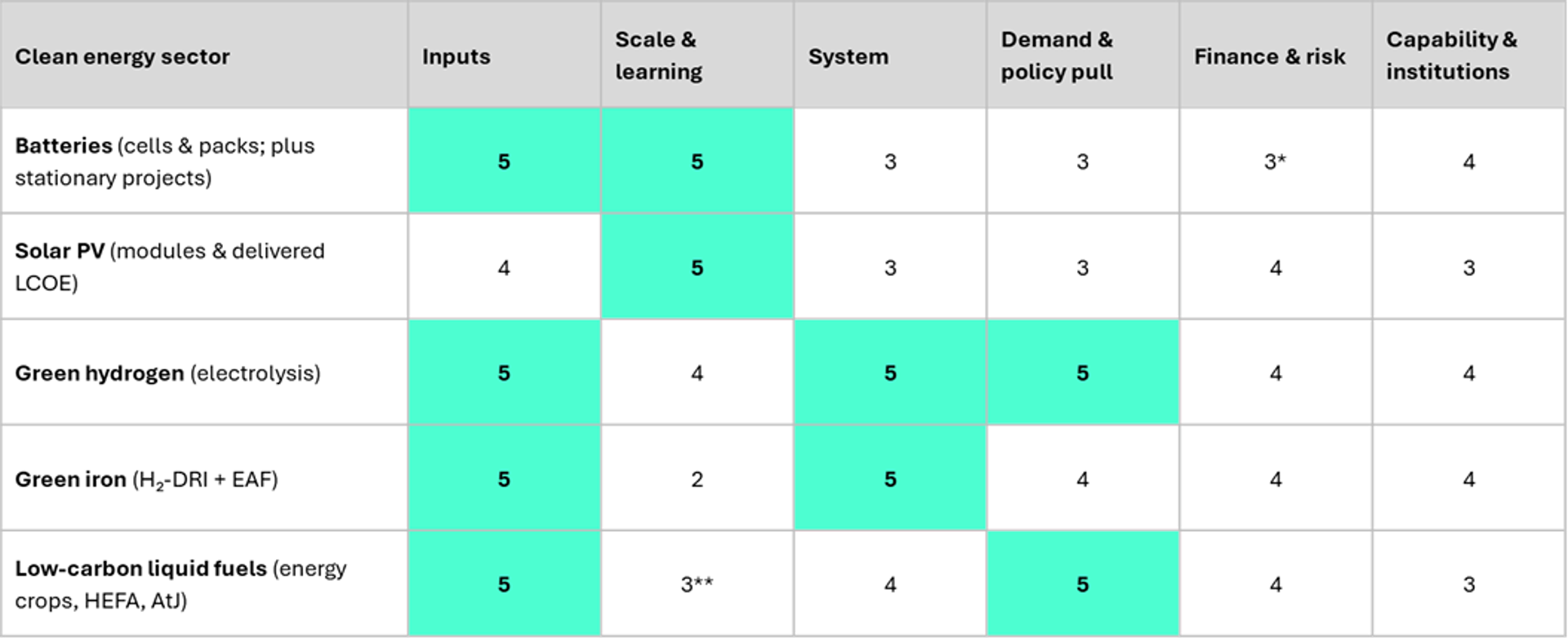

While the six drivers are sector-agnostic; their importance is not. Solar modules and battery cells show famous double-digit learning rates; hydrogen electrolysers have more variable learning; low-carbon liquid fuels often hinge on feedstock cost or demand instruments more than factory learning. Table 1 below shows a comparison of the importance of these different competitiveness factors by sector (see the appendix for further details on the methodology).

Table 1: Importance of drivers to improve competitiveness

Scores indicate how important each driver is to improving competitiveness in that sector over the next 3-7 years (1 = low, 5 = critical). The green coloured cells represent the most important competitiveness sector by clean energy sector.

* For batteries, the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) is higher impact for stationary storage projects than for cell factories.

** Learning is lower for lipid routes and higher for Power-to-Liquid (PtL), netting to ~3 overall.

What really drives competitiveness varies significantly by sector:

- Batteries. Competitiveness is first and foremost a story about inputs and scale. Cathode and anode materials, precursor availability, and factory yields dominate unit costs, so locations that can secure materials and run high-throughput lines at high first-pass yield are advantaged. Because cells are modular and iterate quickly, learning-by-doing remains powerful; repeating standardised lines compounds cost and quality gains. For stationary storage projects, financing terms also matter for delivered $/kWh, but inside the factory gate the big levers are materials, repetition, and know-how. Empirically, lithium-ion learning rates cluster around ~20–24% per doubling.

- Solar PV. Solar still behaves like the textbook case for learning: modules enjoy some of the strongest experience curves in energy technology, with additional (albeit smaller) learning on balance-of-system. Where do these learning effects come from? They come from a range of scale-related innovations such as (a) enhance operational design (e.g., larger ingot/wafer lines and bigger furnaces spread fixed costs); (b) learning-by-doing (e.g., tighter process control, less scrap); (c) process innovations (e.g., thinner wafers, enhanced interconnects); (d) greater use of automation and standardisation; (e) input substitution; and (f) supply chain optimisation. Technology is a driver, but it is technology linked to learnings from operations, as opposed to lab-focused innovation. On delivered LCOE, access to low-cost capital and predictable approvals are almost as important as module cost itself, sensitivity to the cost of capital shows up clearly in LCOE analyses, especially when projects are paired with storage.

- Green hydrogen (electrolysis). Power price and utilisation set the economic floor, so cheap, reliable renewables are the decisive input. Learning does exist, particularly in stacks, and can be amplified by standardised, skid-based balance-of-plant that is repeated across sites. Recent cross-country work finds learning-by-doing ranges for electrolysis technologies typically in the mid-teens to low-30s percent, with wide uncertainty. Offtake is crucial, but the key is to find the segments where green hydrogen is likely to be most competitive. As the well-known “Hydrogen Ladder” by Michael Leibrich has shown, much of the failure of past hydrogen projects has been that they have focused on segments where they do not have the fundamentals to be competitive (e.g., aviation, trucking).

- Green iron (H₂-DRI + EAF). Here, inputs and system dominate. Delivered hydrogen cost and ore/pellet quality drive the economics far more than plant “learning,” while success hinges on hubs that combine abundant renewable power, hydrogen, and logistics (pipelines, high-capacity grid, ports). Learning effects from first-of-a-kind to nth-of-a-kind exist but are likely modest compared with the impact of input prices and infrastructure. Competitiveness therefore follows the hubs: where hydrogen is cheap and reliable, where infrastructure is in place, and where offtake can be contracted. Recent work by Mission Possible Partnership (MPP) and Cyan Ventures has found that demand-side measures supported by two-sided auctions can play an important role in lowering financing costs and the required green premium.

- Low-carbon liquid fuels (energy crops, HEFA, alcohol-to-jet). This sector varies depending on which technology pathway is being considered. Lipid-based routes are largely feedstock-driven (representing up to 80% of total costs), aggregation, quality, and logistics set costs, so learning-by-doing at the plant moves the needle only modestly unless the feedstock story changes. Power-to-liquids routes inherit learning from electrolysers and benefit from repeatable EPC, but they still face a green premium without robust demand signals. Across all routes, credible, standardised offtake (mandates, certificates, book-and-claim) is pivotal: it unlocks finance, justifies supply-chain build-out, and creates the runway for scale. As past work by Cyan Ventures has shown, this can be delivered cost effectively with a well-designed industry mandate scheme.

2. Why learning-rates aren’t a universal test

The temptation in policy design is to look for one simple metric. Learning rates are attractive because they feel rigorous and have terrific case studies (PV, batteries). But they are not a one-size-fits-all justification for early deployment:

- Where learning is proven and modular (PV, cells, parts of electrolysers), early volume is the right lever: it compounds cost drops and performance gains.

- Where input costs dominate (lipid-based fuels; electricity for H₂/DRI), early deployment must target inputs and system bottlenecks (supply chains, hubs, logistics) and demand certainty - not just “build one to learn.”

- Where evidence on learning is variable (electrolysers), early deployment should be tightly linked to standardisation (factory lines, skid-based BoP) and transparent performance data so the public gets the learning it pays for.

This is exactly the kind of “clear fact base” the Commission is asking for when it emphasises least-cost pathways, market-based signals and faster approvals tied to measurable outcomes.

3. What this means for policy

The starting point is diagnosis. Policy should go where it targets the binding constraint for each sector rather than reaching for a single, one-size-fits-all tool. In solar and in cell manufacturing, that constraint is scale: the clearest path to lower costs is to keep factories and project pipelines running at volume with standardised designs and open performance data so learning compounds. In green hydrogen, the pivotal variables are cheap power, high utilisation, and repeatable stacks and balance-of-plant, which only translate into financed projects when there is bankable offtake; the right combination is therefore power-price relief through access to renewable zones, factory-scale equipment programs, and long-term contracts that make lenders comfortable.

Green iron is different. Here, the fastest cost reductions come not from counting on plant learning, but from building hubs where renewable power, hydrogen production, and ore logistics co-locate, and where steel offtake can be contracted under credible standards or trade frameworks. Public spending is most effective when it underwrites enabling infrastructure and risk-sharing mechanisms that reduce WACC while hydrogen costs fall, rather than scattering one-off FOAK plants that cannot operate competitively. Low-carbon liquid fuels underscore a different lesson. For biofuel pathways, the economic centre of gravity is feedstock access and logistics, so early intervention that solves for innovation in feedstocks, aggregation, quality, and certification can do more for competitiveness than generic capital grants. For power-to-liquids, the case for early deployment strengthens when it is tied to standardised electrolyser and EPC packages, cheap renewable power, and demand instruments that bridge the green premium long enough for costs to come down.

The National Interest Framework guiding the Future Made in Australia (FMIA) strategy give high-level consideration to these competitiveness factors, but the devil is in the detail, and in some nascent areas, such as low carbon liquid fuels, there are clear gaps (e.g., a lack of a clear demand signal such as a mandate). So, we suggest two recommendations for policymakers based on this analysis:

1. Review policy approaches in light of these competitiveness factors. A review of existing government support, particularly in priority sectors such as green iron, green hydrogen, clean tech supply chains, and low carbon liquid fuels, should be conducted to ensure that actions are targeting these competitiveness factors. Our belief is that this exercise will throw up some important gaps.

2. Be clear on what success looks like. Across all of these sectors, support should be tied to measurable outcomes that mirror the underlying constraint. Where learning is the lever, publish experience-curve metrics, like stack dollars-per-kilowatt against cumulative deployments, and taper support as costs fall. Where inputs and systems dominate, track delivered input costs, interconnection and pipeline lead times, and logistics performance, and make policy conditional on progress.

A final note. None of this works without predictable, timely approvals. Time is a hidden tax on competitiveness, raising financing costs and eroding the gains from engineering, so approval reform with clear service levels is not an optional extra; it is part of the cost base.

Designing policy this way meets the Commission’s test: it explains precisely why an intervention is needed, what constraint it will relax, and how we will know that it worked. It also creates a built-in exit ramp. Where learning is strong, support should step down automatically; where public goods justify ongoing help, energy security, early supply chains for hard-to-abate sectors, assistance should be targeted and performance-linked. Different tools for different jobs, all anchored in the specific drivers of competitiveness rather than generic labels.

Appendix — methodology on sector assessment of drivers

Each of the drivers are ranked from 1 (not critical) to 5 (critical) for each sector. While it is hard to be precise with such assessments, below is the thinking behind the numbers in this report.

Inputs (feedstocks, power, ore, labour)

- Critical (5): Variable inputs are >50% of cost and vary widely by location (e.g., electricity for green H₂/DRI; lipids for HEFA SAF; cathode metals). Security is uncertain.

- Low (1): Inputs are a small cost share or easily contracted; regional price spreads are narrow.

Scale & learning (experience curves)

- Critical (5): Modular, manufactured tech with fast iteration and credible ≥10–20% learning per doubling; FOAK to NOAK gap >20%.

- Low (1): One-off, bespoke projects with long cycles; costs set by site/fuel rather than replication.

System (infrastructure & logistics)

- Critical (5): Dedicated networks (H₂/CO₂, high-capacity grid, ports, storage) and scarce EPC capacity bottleneck deployment; interconnection/pipeline lead times >24–36 months.

- Low (1): Plug-and-play into existing infrastructure; logistics simple; EPC abundant.

Demand & policy pull (offtake, standards, CfDs)

- Critical (5): No established market or big green premium; long-term contracts won’t sign without mandates/credits/standards.

- Low (1): Product at/near parity in deep merchant markets; standard contracts exist; compliance demand is durable.

Finance & risk (WACC)

- Critical (5): Capital-intensive, long payback, novel tech or volatile revenues; a 1-pp WACC swing moves LCOx ≥5–10%.

- Low (1): Opex-dominated, contracted cashflows with investment-grade counterparties; stable policy means WACC near sovereign + modest premium.

Capability & institutions (skills, permitting, governance)

- Critical (5): Scarce tacit know-how (yields, QA/QC), tight labour markets, unpredictable permitting, or weak contract enforcement.

- Low (1): Mature skills base, predictable permits, robust quality systems and dispute resolution.

- Dr. Fraser Thompson

Need a problem solved? Let`s work together to solve it

Contact UsShare with